Sixty Years of the Beltway: The National Capital Planning Commission and Washington's Demographic Revolution

Who Decides What Washington Looks Like? Part 4

Read Part 1 of this series, “Bringing the City Beautiful to Life,” here.

Read Part 2 of this series, “Shaping Washington for a Century,” here.

Read Part 3 of this series, “Segregation and Community Cooperation,” here.

Sixty years ago this August, the Capital Beltway was completed, forever transforming the Washington, D.C., area. Anyone stuck on the Beltway on a broiling summer afternoon, as I was this past week, might well curse the planners who condemned Washingtonians to endless standstill traffic, never-completed construction, and the dread of mistiming one’s entry onto what can feel like one of Dante’s nine circles of Hell.

Yet the Beltway, for all its blood-pressure raising frustration, was one of the critical pieces of Washington’s development as a global city, fueling the type of growth throughout the region that the post-World War II capital required to wage a worldwide struggle during the Cold War. That the Beltway engendered dramatic urban renewal and helped drive Washington’s fundamental demographic transformation only illustrated the way in which the District’s urban development was shaped by, if not subordinated to, national interests.

The Beltway’s origins hark back almost a century. The National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC) was established in 1924 to purchase land for Washington, D.C.’s parks but soon took on a comprehensive planning role for the Capital’s park system, parkways, and playgrounds. While its main responsibility was for maintaining and improving green space, it soon became involved in some of the most radical restructuring of the urban landscape in Washington’s history.

The most far-reaching as well as controversial of NCPC activities have been related to transportation, urban renewal, and particularly the highway building projects of the 1950s and 1960s. As early as the late-1920s, the Commission grappled with understanding how the rapid growth of automobile ownership would affect a fairly compact, dense urban core. NCPC’s “Report on a Major Thoroughfare System and Traffic Circulation Problems of Washington” (1927) began a process of exploring and promoting a system of both circumferential (what we would now call ‘beltway’) and radial roads that would push development out of the increasingly crowded city and into the surrounding rural areas.

The unprecedented growth of Washington during World War II, and the realization that America’s informal Cold War empire would make permanent what some called the ‘national security state,’ presented NCPC with changes it could not control, but could try to shape. From 1940 to 1948, the population of the Washington Metropolitan Area increased from just under 968,000 to 1.4 million, and the District itself saw a 30 percent increase, per the U.S. Census. With Washington’s infrastructure bursting at the seams and few undeveloped areas left, the NCPC’s comprehensive plan of 1950 recommended the building of highways throughout the region that would facilitate a shift out to the suburbs for white-collar workers, while leaving lower-income workers in older urban areas and in some cases reinforcing or creating new segregated neighborhoods.

At this juncture, urban planner Harland Bartholomew, who had worked intermittently with NCPC since 1920, took over as chair of the Commission in 1953. Bartholomew, whose firm had contributed to the 1950 comprehensive plan, was an early proponent of highway construction and “slum clearance” as tools for urban revitalization. His goals would guide NCPC as it faced a reckoning over Washington’s urban development and transportation needs. Initially accepted, Bartholomew’s views soon became controversial as their cost became clear.

Some elements of NCPC’s plans were seen as simply common sense responses to emerging conditions. As government agencies began to move out of the District and into rural areas around Washington, and as the continued expansion of automobile ownership made practical the growth of suburban areas, NCPC embraced the need for new transportation corridors. By 1959, a concrete proposal for more than 300 miles of new roads started to reshape the National Capital Region, including the Capital Beltway (I-495), which was approved in 1955, and the Southwest Freeway.

The Beltway transformed Washington, dramatically fueling the expansion of suburbs in Maryland and Northern Virginia. The first sections of the Beltway were opened in late-December 1961, linking Alexandria, Virginia, and Oxon Hill, Maryland, via the new Woodrow Wilson Bridge across the Potomac. By its completion, the Beltway was a 64-mile circumferential loop, dramatically improving accessibility around the region but quickly becoming infamous for its congestion. The final section of the Beltway was opened on August 17, 1964, sixty years ago this summer. The opening day ceremonies gave a taste of what was to come, as a two-mile-long line of cars waited at the New Hampshire Avenue exit to make the triumphant loop; it took over 20 minutes to clear the traffic jam.

(Opening of the last section of the Capital Beltway, August 17, 1964, traffic jam in background; original image from DC Public Library; NCPC centennial exhibit.)

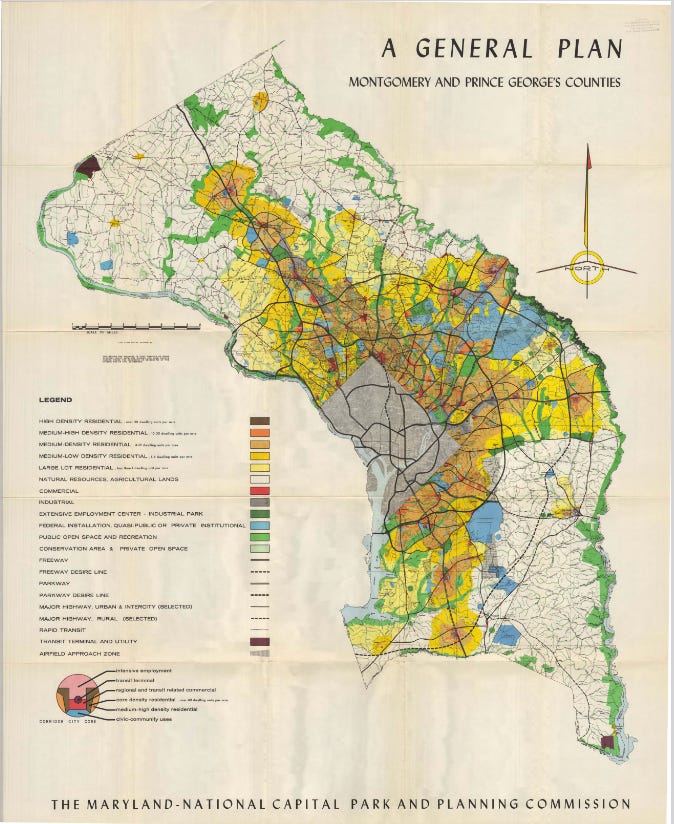

As the Beltway neared completion, the question of suburban planning came to the fore. The Maryland-National Capital Parks and Planning Commission promoted intensive commercial development along new highway “corridors” that radiated out from the Beltway, while maintaining open space and encouraging less dense development in the residential “wedges” in between, most notably in Montgomery County.

(Map of General Plan for Montgomery and Prince George’s Counties, from “…On Wedges and Corridors” (1964), Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission)

This planning enabled startling growth of Washington’s suburbs, and while ultimately adding to the congestion of the Capital region, it also ensured that a fairly orderly process of growth could occur. Montgomery County more than doubled in size, from 164,400 people in 1950 to nearly 341,000 just a decade later, comprising both emigres from the District but also thousands of new residents drawn by the growth of Cold War Washington. Talented scientists, mathematicians, lawyers, physicians, accountants, historians, and other trained professionals flocked to Washington as government grew in response to the division of the postwar world. The new suburbs that arose to house these cold warriors, such as Kemp Mill, in Montgomery County, and the planned Reston community in Virginia, added thousands of new homes, dozens of new schools and parks, and hundreds of stores and shops outside Washington—all linked to each other and the governmental core in the District by the new roadways planned by NCPC.

Yet the other side of this story was a fundamental demographic transformation of Washington that opened a new era in the District’s history. As calculated by historian Matthew Gilmore, Washington, D.C., saw a net decrease of only 40,000 residents from 1950 to 1960, but that hides a dramatic demographic shift. In that decade, Washington’s White population plummeted by a full third, from 517,865 to 345,263, a decrease of 172,602 persons. In the same period the Black population rose from 280,803 to 411,737, an increase of over 130,000 persons, many of whom were part of the final years of the Great Migration from rural southern areas northward. From 1960 onward, Washington was a majority Black city, yet still run by government-appointed White commissioners, leading to a new set of questions about self-government, economic opportunity, civil rights, and urban development that would fuel the demand for Home Rule during the turbulent 1960s.

This transportation and residential revolution also forced the question of urban renewal inside the District. In practical terms, that came to mean the destruction of long-settled neighborhoods for redevelopment or for replacement by throughways leading out to the new growth areas. These renewal plans became particularly controversial in the 1950s and 1960s over the clearing of lower-income, ethnic, and largely Black areas in Southwest Washington and in Anacostia. As viewed by NCPC and other District officials, including commissioners, renewal was justified partly to facilitate new highways leading to Virginia, and partly because such areas were deemed obsolete or blighted, something long advocated by NCPC Chair Bartholomew. Since the growth of suburban Maryland and Northern Virginia had led to an emigration of Whites from Washington and left it a majority minority city, the question was not just an urban one, but also a racial one.

(Urban renewal in Southwest D.C., late-1950s; “Washington Post” image from the NCPC.)

By 1952, NCPC and the District’s Redevelopment Land Authority presented competing plans for the redevelopment of a 113-block area in Southwest, along the Washington Channel, bounded by C Street on the north, 12th Street on the West and South Capitol on the east. Few argued that the area had not been neglected and was not in need of safer buildings and more public amenities. In February 1952, the Washington Post noted that nearly half the structures examined were deemed substandard. The question was whether they, and by extension their neighborhood, could be preserved in some fashion or would be demolished for new construction.

According to urban historian Frederick Gutheim’s history of NCPC, the Commission’s own studies, written by historian and commission member Elbert Peets, expressed a preference for preserving and rehabilitating older Southwest neighborhoods as much as possible. While Peets wanted to preserve existing shopping streets and open up green space, the Redevelopment Land Authority and its expert, Arthur Davis, preferred building modern “super blocks” that would require large-scale demolition. The Commission mostly lost the battle to Davis’s more radical urban renewal approach. The resulting displacement of roughly 23,000 mainly low-income Black residents in favor of modernization and new residential clusters fed resentment for decades. Many of the older, minority residents could not afford to buy or rent in the new developments, which no longer reflected the neighborhood’s historical character.

Eventually, civic protest in the 1960s halted further destruction of neighborhoods, and specifically truncated plans for building a complete freeway Inner Loop that would have cut a swath through Northwest and Northeast D.C. Instead, the multilane I-395 expressway was abruptly stopped at New York Avenue, east of the Capitol and just north of the 3rd Street Tunnel. NCPC Chair Libby Rowe (highlighted in Part 3 of this series) shifted the Commission’s support away from further development of highways and the destruction of neighborhoods towards historic preservation and a subway/regional light rail system, which Rowe called the “salvation of the center of the city,” and which eventually became the Washington Metro.

Even with this new focus, the transportation revolution had permanently changed Washington. The suburbs pushed inexorably farther into Maryland and Virginia, the Beltway remained overburdened, Metro continually struggled for funding from the three jurisdictions that oversaw it, and the District remained strongly divided between affluent and lower-income areas. Yet NCPC’s efforts resulted in more comprehensive planning of this process than otherwise likely would have occurred, given that two states and the D.C. municipal government would all maintain independent interests.

The dramatic, and many would say unnecessary, urban renewal plans in Southwest eventually led to a reaction that jumpstarted greater cooperation between central planning bodies, such as NCPC, and local communities and also placed conservation at the center of urban planning. By the early 1970s, groups such as the DC Preservation League had formed to add grassroots voices to Washington’s development debates. As these groups and commissions interacted, collided, and cooperated, Washington’s messy, never-ending process of development slowly settled on a reasonable balance. Thanks to their efforts, and the work of guiding bodies like NCPC, Washington has more green space per capita than nearly any other city in the nation, infrastructure largely has kept pace with growth, and the grand vistas that define the National Capital have been preserved.

After a century, NCPC’s planning continues. Competing notions of public space, historic monuments, and needed development are still poured into the crucible of the formal planning process. In 1997, the NCPC released the “Legacy Plan,” which attempted to set a long-range vision for the National Capital Region in the 21st century, including unifying the city and the monumental core with the U.S. Capitol at the center; integrating the Potomac and Anacostia Rivers into the city’s public life; and protecting the Mall, East and West Potomac Parks, and adjacent historic buildings from future development.

As the Commission actively reinterprets its activities over the past century, Executive Director Marcel Acosta wrote in an email that "The National Capital Planning Commission's Centennial offers a moment for both celebration and reflection. By learning from our successes and mistakes, NCPC has focused on being better neighbors by working collaboratively with local partners as we re-envision the future of downtown Washington, D.C., and this region."

There was good reason José Correia da Serra, Portuguese minister to America in the late-1810s ironically called Washington the “City of Magnificent Distances.” Back then, its uncleared fields, cow trails, and straggling buildings had barely begun to live up to the vision of Washington’s founders. Today, staring down the Mall from the Capitol or looking across the Potomac from the Lyndon Baines Johnson Memorial Grove, the magnificent distances are no longer something to scoff at. L’Enfant’s plan may not be fully completed, large sections of the city still lag in opportunity, and the region as a whole feels too crowded and too expensive, but a century of work by the National Capital Planning Commission has brought Washington far closer to becoming the City Beautiful than many thought would ever happen.

More Reading: As far as I know, there is only one full-length study of the history of the Capital Beltway: Jeremy Louis Korr, Washington's Main Street: Consensus and Conflict on the Capital Beltway, 1952-2001 (PhD dissertation, University of Maryland, 2002). A brief, online popular history of the Beltway is here. Among the planning documents for Southwest Washington are the 1952 and 1956 proposals. The 1964 suburban “…On Wedges and Corridors: A General Plan” is here.

Imagine if they had built the out beltway. In Boston, there’s 128/95, the inner ring road and 495, the outer one. Both suffer from being over capacity but not as badly as the beltway around DC. The photo of the Jefferson memorial from the 1950’s is remarkable for all the open space.