Shaping Washington for a Century: The National Capital Planning Commission Turns 100

Who Decides What Washington Looks Like? Part 2

Read Part 1 of this series, “Bringing the City Beautiful to Life,” here.

Washington, D.C., may never have been a sleepy town, but up through the Great War, it was undeniably a Southern one; grown since the Civil War, but still a slow-paced, largely inward-looking capital. The sudden and dramatic expansion called forth by America’s entry into World War I forever transformed the District, turning it into a global capital in the space of barely eighteen months.

The influx of hundreds of thousands of war workers, specialists, experts, enthusiastic men and women alike, was captured by Helen Nicolay, daughter of Abraham Lincoln’s secretary, John, in her elegiac history of Washington, Our Capital on the Potomac, written in 1924:

Every one…moved briskly,…as if hurrying to tasks in which they had vital concern…the avenue full of eager figures…[a] new spirit and the rushing to untried tasks…The great Union Station swarmed, day and night…(pp. 514-15).

Yet Nicolay noted, at least wistfully, if not sadly, that the capital she had grown up in, the Gilded Age city of the “cave dwellers” and eccentrics like Henry Adams, was now gone forever:

Washington has never returned to its pre-war habits. It never can, any more than it can shrink again to its pre-war size. For a time we hopefully looked forward to the day when all would be as it had been. But…we realized that the leisurely town we loved had changed to a busy city…Old Washington vanished, never to return…(p. 517).

The “tempos” on the National Mall and in front of Union Station, the hastily-thrown up housing, the congestion of trucks and cars on the streets, all not merely changed daily life, they threatened the revitalized vision for the National Capital embodied in the 1902 McMillan Plan and its influences in the “City Beautiful” movement.

By the early-1920s, as older neighborhoods became denser and new housing pushed out toward the city’s boundaries, calls for parkland and open space became louder. These demands were supported by the city elite, including members of the powerful Board of Trade. Though the Commission of Fine Arts and the Public Buildings Commission continued to work with the Army Corps of Engineers and the D.C. municipal government to review proposals for the Capital’s development, the need for a central body to purchase land to try and fulfill the goals for Washington’s park system was evident.

In response, Congress authorized the National Capital Park Commission on June 6, 1924, “to provide for the comprehensive systematic, and continuous development of the park, parkway, and playground system of the National Capital.” Simply purchasing land was soon seen as insufficient to ensure the type of development envisioned under the McMillan Plan, and two years later, the body was reestablished as a comprehensive planning agency under the name of the National Capital Park and Planning Commission. In 1927, the Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission was formed, to rationalize planning for Montgomery and Prince George’s Counties adjacent to the District. Upon the Commission’s reestablishment in 1926, Frederic A. Delano served as its president and most powerful member. Delano was particularly influential, having been a railroad president, first vice chairman of the Federal Reserve, and president of the American Planning and Civic Association, not to mention uncle of Franklin Delano Roosevelt. He served on the Commission until 1942, when he resigned in a letter to his nephew.

Known today as the National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC), the body describes its mission as being to

protect the integrity of the national capital’s built and natural environments and serve as guardians of Washington’s extraordinary design, culture, and historic legacy…

It does so by serving as

the federal government’s central planning agency for the National Capital Region. Through planning, policymaking, and project review, NCPC protects and advances the federal government’s interest in the region’s development. The Commission provides overall planning guidance for federal land and buildings in the region…

Throughout its history, the Commission has focused on expanding green space, maintaining Washington’s sweeping vistas and lines-of-sight, building and enhancing ceremonial corridors, and eliminating obsolete infrastructure.

The Commission is not elected, but is comprised of twelve commissioners, three appointed by the President, two by the Mayor of Washington, D.C., and seven ex-officio from the Executive and Legislative Branches, usually represented by alternates. A staff of urban planners, architects, designers, and other professionals carries out studies, oversees long-range planning for future development, and provides recommendations on submitted projects. The overlapping planning done by NCPC itself can be confusing to the public, let alone when combined with crossover from other federal and District bodies. In addition to a four-year Strategic Plan to set overall goals, the most important product of the Commission is the “Comprehensive Plan for the National Capital,” comprised of two sections, Federal Elements and District Elements, that look ahead over two decades.

Given Washington’s unique position as the seat of federal government, urban planning in the District is permanently entwined with questions of national history and symbolism, the needs of the non-government areas of the city, and ensuring that the executive and legislative branches have the infrastructure they require to do the people’s business.

The Commission doesn’t have unilateral authority to approve projects, as there is a web of federal and municipal bodies that ultimately determine what gets built where (or doesn’t) in Washington. Among the main partners for NCPC are the Commission of Fine Arts and the National Park Service’s National Capital Memorial Advisory Commission. However, NCPC’s unique remit in defining and protecting federal interests gives it particular power and can put it at odds with municipal authorities focused on economic and commercial issues.

In balancing the need to preserve the unique public space of the Capital with the development required to ensure economic vitality, NCPC has regularly interacted with the most influential business and civic bodies in Washington, including the Board of Trade, started in 1889; the Chamber of Commerce, which was formed in 1938 to serve Black-owned businesses; and the Federal City Council, founded in 1952 by then-Washington Post publisher Philip Graham as a new citizens’ committee. NCPC has also worked with the Committee of 100 on the Federal City, comprised of leading residents of the District, which was established just a year before the Commission and whose founding president, from 1923-1944, was NCPC’s head Frederic Delano.

Among NCPC’s most important, and visible, responsibilities is being one of the planning bodies that approve commemorative works in the District. The stateliness of Washington’s monumental architecture hides an often contentious, and sometimes bitter, process of putting an official stamp of approval on public buildings and monuments. From its inception, NCPC has worked closely with the Commission of Fine Arts and the National Park Service on reviewing plans and designs, some which today are so iconic that it’s surprising to learn were controversial at the time. Being in existence for over a century, both bodies have had to negotiate the dramatic shifts in aesthetics during the 20th century, from neo-classicism to modernism and through post-modernism.

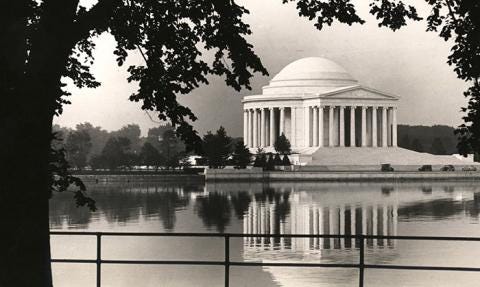

(Jefferson Memorial; image from Commission of Fine Arts)

One of the great aesthetic dust-ups occurred during the late-1930s over the proposed Jefferson Memorial. NCPC was skeptical about the memorial’s isolated location across the Tidal Basin, while the CFA opposed “architect of empire” John Russell Pope’s neo-Pantheon design. In the end, President Franklin D. Roosevelt forced the acceptance of both the location and Pope’s design, and what FDR called a “shrine to freedom” at its dedication in 1943 became one of Washington’s iconic and beloved public spaces. Despite its success, the Jefferson Memorial was the last great Beaux Arts monument built in Washington.

Like other bodies charged with overseeing public monuments, the Commission has navigated changing trends in taste and aesthetic value. In 1981, Yale University architecture student Maya Lin’s design for the Vietnam Veteran’s Memorial in Constitution Gardens set off a firestorm, with many traditionalists lambasting the stark black wall of polished granite cut into the earth, while others praised its emotional power. Yet the extraordinary popularity of the memorial proved the wisdom of NCPC and other bodies in approving the design. In doing so, NCPC helped redefine the nature of public memorials, along with the National Park Service and the Commission of Fine Arts.

(Vietnam Veterans Memorial; image from The Cultural Landscape Foundation.)

Not all monuments approved by NCPC and its fellow planning bodies have been similarly embraced as the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. Architect Frank Gehry’s proposed memorial to President Dwight D. Eisenhower received significant criticism, panned as too abstract and misdirected. Moreover, the site’s location was also controversial, finally being located in front of the U.S. Department of Education building and cutting across a blocked section of Maryland Avenue. Though initially given the go-head in 2000, the memorial was put in limbo when Congress halted funding for the memorial for several years after negative comments by the public and members of the Eisenhower family. Ultimately, revisions led to the approval of the modernist design by groups including NCPC, CFA, and NPS in 2015, but failed to placate critics such as the National Civic Art Society.

(Dwight D. Eisenhower Memorial; image from National Park Service.)

With the ever-expanding constellation of public memorials in Washington, the struggles over space and style continue. While Americans seem to want ever more memorials, few want to see the National Capital resemble the ancient Roman Forum, with its disorganized jumble of temples, altars, arches, and statues. As battles over remembering America’s past continue to flare up, NCPC’s role in the civic dialogue as important as ever, perhaps even more so.

Yet as public as is NCPC’s activity in approving commemorative works, the Commission has had an even more profound, if hidden, effect on the very fabric of Washington’s neighborhoods and the structure of daily life in the National Capital.

Read Part 3 of this series: “From Segregation to Community Cooperation in the National Capital.”

Further reading: The most comprehensive discussion of NCPC is by urban historian Frederick Gutheim and Antoinette Lee, Worthy of the Nation: Washington, D.C., from L’Enfant to the National Capital Planning Commission, 2nd. ed. (Johns Hopkins, 2006). The Commission’s website has a centenary page with links to a fascinating online planning library of key documents, a centennial exhibit, and an oral history archive.