From Segregation to Community Cooperation in the National Capital

Who Decides What Washington Looks Like? Part 3

Read Part 1 of this series, “Bringing the City Beautiful to Life,” here.

Read Part 2 of this series, “Shaping Washington for a Century,” here.

Washington, D.C., is one of America’s greenest cities, with parks tucked into city corners, sweeping along the Potomac riverfront, and stretching up into sprawling Rock Creek Park and beyond, into Maryland. Since 2020, the District has been ranked as the best big-city park system in the United States by the Trust for Public Land. The century-long efforts of the National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC), along with partners like the National Park Service (NPS), have resulted in fully 24 percent of the land in Washington reserved for public parks. NPS manages over 90 percent of those parks, more than 350 properties covering over 6,700 acres in the District of Columbia. This horto in urbs and grandeur of the city’s monumental core attracts tens of millions of visitors each year.

(Constitution Gardens; image from The Cultural Landscape Foundation.)

Yet while parks and monuments are public, and shared by residents and visitors to Washington alike, NCPC also has profoundly influenced daily life for the District’s residents. Its less visible but powerful authority over the shape of the city has affected and often altered the communities in which Washingtonians live. In pursuit of its mandate to increase green space and guide Washington’s transportation system, NCPC has played a role in determining the livability as well as the survival or destruction of the District’s neighborhoods, in a sometimes-controversial, often-evolving role.

Segregation, Community Cooperation, and the Evolving Role of NCPC

The effect on urban renewal and development that NCPC has played over the past century is inextricable from the history of race in Washington. The Capital has at times been a laboratory in race relations, sometimes led and sometimes hindered by the federal government. An influx of escaped or freed slaves to Washington during the Civil War, the so-called “contrabands,” numbered 40,000 by 1865 and the end of hostilities. These arrivals strained the city’s infrastructure and services and led to tensions with the long-established free Black elite of the Capital.

In December 1866, Radical Republicans forced through unrestricted manhood suffrage for District municipal elections in December 1866, presaging a plan to give Blacks the vote throughout the Union. Federal employment of Blacks increased in the last decades of the 19th century, as well, though most of the jobs were menial and only a few rose to the level of government clerks. Despite that, in 1891, 2,400 Blacks worked in government service, out of a total of 23,144 federal employees (Green, “The Secret City,” p. 129). Though Blacks faced more overt discrimination in District jobs (for example, out of 731 policemen in 1908, only 39 were Black), some city positions in essence became reserved for them, such as District Recorder of Deeds.

Despite these hesitant efforts, Washington’s municipal governments and residents steadfastly opposed greater equality, in part from resentment that Northern congressmen who would not have supported desegregation at home were pushing it on the powerless District. The tide of equality began to recede as early as the second Cleveland Administration and the Panic of 1893, when employment dropped nationwide. Soon, what small gains Blacks had made were undone by the re-segregation of the federal workforce in the 1910s and 1920s, especially during the administration of President Woodrow Wilson. At both the federal and District level, Blacks were removed from more meaningful positions, including those like the District Recorder of Deeds.

Accompanying this labor force reversal was a more formalized segregation within the District itself, where the Black percentage of the total population fell to just one-quarter by 1920. This loss of the community’s political and economic power was reflected in how the city evolved in the first half of the 20th century. As segregation was intimately involved with urban planning, the National Capital Planning Commission was drawn into the process as it pursued the increase of greenspace in Washington.

Some NCPC plans, such as for a park at Fort Reno, removed long-established mixed-race and Black neighborhoods and in essence created exclusive areas for Whites, since neighboring subdivisions were either too expensive for minorities to buy into or maintained restrictive covenants, or lenders refused to underwrite housing loans (also known as “redlining”) in predominantly White areas. The action at Fort Reno was particularly drawn out, lasting from the mid-1920s through the early-1950s, taking decades for Congress and the District to approve plans to buy out landowners, condemn and tear down older housing, and redevelop the core of the neighborhood into a large public park.

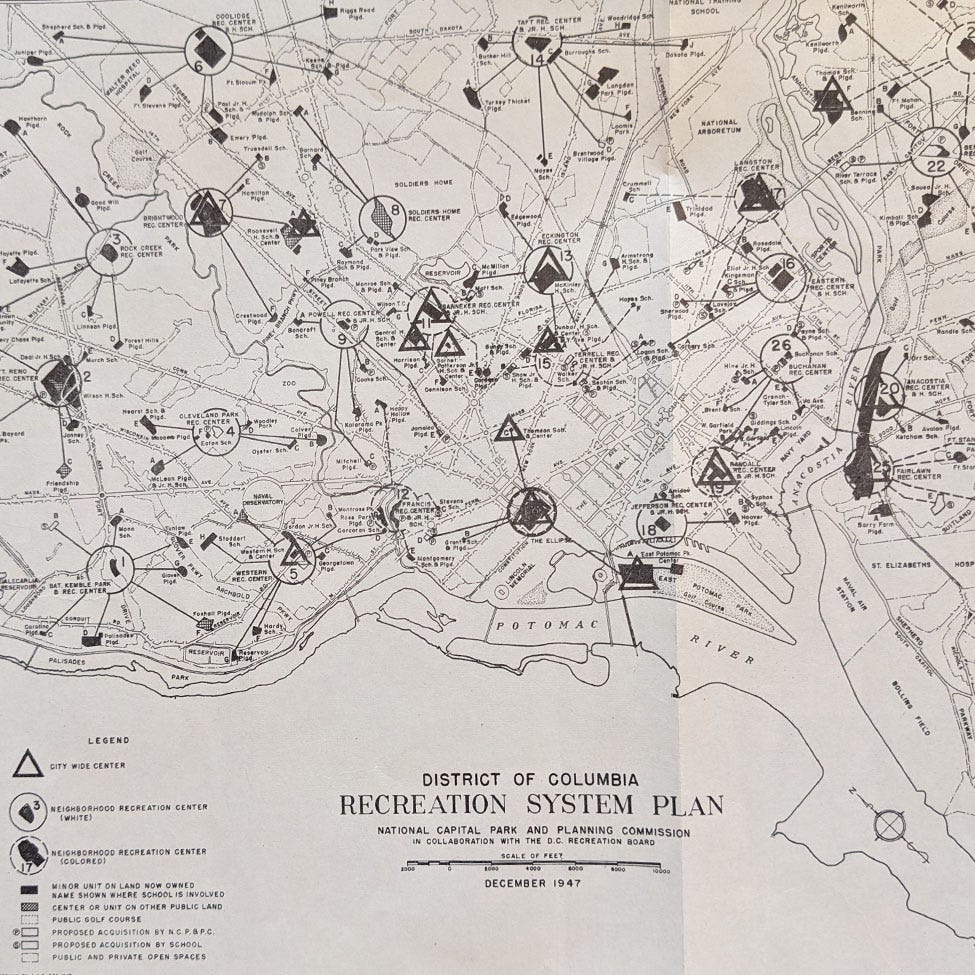

Postwar desegregation in Washington was led, if unevenly, by the U.S. Government. In 1945, the U.S. Department of the Interior declared a policy of “non-segregation” on all its property, including those areas in the District managed by the National Park Service. Two years later, NCPC created a map for the District’s Recreation Board that showed Washington’s planned recreation system divided into 26 areas of parks and recreation centers, some of which were on federal property. Despite Interior’s non-segregation policy, the District chose to keep playgrounds and most of the community centers segregated. Of the twenty-six recreation centers, fully eighteen on NCPC’s 1947 map were reserved for “Whites,” including all the ones in Northwest, D.C., and in Rock Creek Park, while the remaining ones were labeled “Colored” (dashed-line circles on the map below). A separate set of seven “city-wide centers” presumably were integrated, while others were co-located with segregated facilities (a few centers cannot be located on the map reproduced in NCPC’s online planning library).

(District of Columbia Recreation System Plan, 1947; image from NCPC)

After extensive interagency discussion, the NCPC’s map was revised in 1949 to show a racially-integrated park system, in conformity with the National Park Service’s policy, but the District maintained segregation of playgrounds and pools. This system of partial segregation of public common grounds lasted until 1954, when in the wake of Brown v. Board of Education, the Recreation Board immediately desegregated all of Washington’s playgrounds and community centers.

By the 1960s, NCPC had embraced a new approach to neighborhood redevelopment, responding to new civic activism in the District. The Commission’s new attitude was due in no small part, as well, to its new chair, Elizabeth “Libby” Rowe. Rowe, wife of Democratic lawyer and political appointee James H. Rowe, Jr., was appointed the first female commissioner on NCPC, in 1961, by John F. Kennedy, and soon became its chair, serving until 1968.

(Elizabeth “Libby” Rowe, NCPC Chair, 1961-68; image from NCPC.)

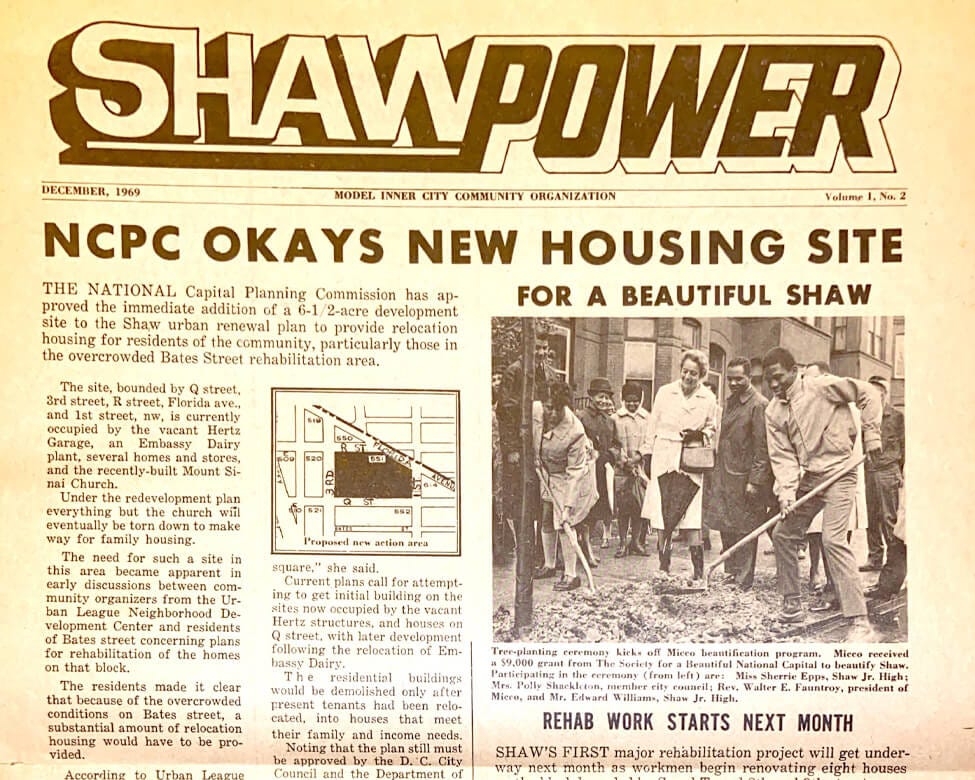

Rowe opposed the wanton destruction of historic areas for redevelopment, and under her leadership, NCPC began working with some minority civic groups to preserve historic neighborhoods and ensure that redevelopment did not mean expulsion of Blacks. A notable effort in this regard was the attempt in the late-1960s to redevelop the Shaw neighborhood in Northwest, which includes Howard University and was the home early in the 20th-century of Duke Ellington and pioneering Black historian Carter G. Woodson. NCPC worked closely with the Rev. (later Delegate) Walter Fauntroy’s Model Inner City Community Organization (MICCO) to save much of Shaw’s historic character and prevent forced displacement.

(MICCO newsheet on Shaw renewal, 1969; image from NCPC.)

Libby Rowe was one of the most consequential NCPC Chairs, cementing the Commission’s focus on ensuring planning in Washington looked to represent all constituencies and making the public’s interests paramount. She led the Commission’s efforts in the 1960s to maintain the District’s historic Height of Buildings Act and thereby protect the lines of sight and grandeur of Washington’s monumental core. She established Washington’s first official historic preservation efforts through the founding of the Joint Committee on Landmarks in 1964 by NCPC, the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts, and the District Government. Rowe also supported First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy’s efforts to rebuild and restore historic Lafayette Square and worked with Lady Bird Johnson on her Committee for a More Beautiful Capital, which developed small parks and planted new acres of trees and flowers throughout Washington.

NCPC and America’s “Main Street”

While segregation and urban renewal of older neighborhoods have been among the most challenging issues facing NCPC, other long-festering problems of how to shape Washington also have been dropped into the Commission’s lap. One of the most enduring is also one of the most visible to tourist and resident alike. Since the Kennedy Administration, the federal government has struggled to create both a historically-preserved and economically-vibrant Pennsylvania Avenue corridor between the Capitol and the White House.

The site of presidential inaugural parades and funerals, festivals, and other major public events, as well as enclosing the northern side of the Federal Triangle, Pennsylvania Avenue holds first place among the nation’s famed thoroughfares. Yet, it has surprisingly lagged in having a coherent development scheme. The neo-classical Federal Triangle buildings stand opposite the brutalist FBI Headquarters, and for years the avenue was described as “drab and depressing” or “shabby.” First Ladies Jackie Kennedy and Lady Bird Johnson were both deeply involved in efforts to improve Pennsylvania Avenue, yet successive plans have failed to achieved the goal of turning it into “America’s Main Street.”

(Photo by author.)

In 1972, Congress established the Pennsylvania Avenue Development Corporation (PADC) to revitalize the avenue. The PADC’s 1974 “Pennsylvania Avenue Plan” noted Congress’s determination that the Avenue

…be developed and used in a manner suitable to its ceremonial, physical, and historic relationship to the legislative and executive branches of the Federal Government, and to the governmental buildings, monuments, memorials and parks in and around the area.

The Plan spearheaded a number of improvements to make the Avenue “a link between the governmental city and the private city.” These included increasing space for public gatherings on the Avenue, including Freedom Plaza, while earlier decisions to destroy some historic buildings, such as the Old Post Office, were abandoned. Bolder goals, such as increasing commercial opportunities and bringing people back to live along the Avenue, however, failed to pan out.

By 1996 Congress had dissolved the PADC, turning over planning for the Avenue’s future to NCPC, NPS, and the General Services Administration (while the District of Columbia’s Department of Transportation maintains the physical roadway). In the latest attempt to create a comprehensive and viable plan for the area, NCPC’s “Pennsylvania Avenue Initiative,” envisions at least a decade of preparation before any major changes begin to take shape. After two-and-a-quarter centuries, Pierre Charles L’Enfant’s vision for the great boulevard of the monumental core has not yet fully been realized, and NCPC’s efforts to fulfill his ideas continue.

Perhaps the most consequential and controversial of NCPC’s actions, however, has been its role in reshaping Washington’s transportation network and the resulting developmental and demographic revolution it engendered. Driven by 1950s chair Harland Bartholomew, these postwar plans fundamentally reshaped National Capital Region.

Read Part 4 of this series: “Sixty Years of the Beltway: The National Capital Planning Commission and Washington's Demographic Revolution.”

More Reading: A recent NCPC report on Washington’s green space, with excellent maps and statistics, can be found here. NCPC Chair Harland Bartholomew’s history of urban planning in Washington, written in 1958, can be found here; the next post will discuss Bartholomew’s controversial legacy. For more on Libby Rowe, see the transcript of an interview from the LBJ Presidential Library. The 1974 Pennsylvania Avenue Plan is here. Among the many books on racial relations in Washington, see Chris Myers Asch and George Derek Musgrove’s comprehensive Chocolate City: A History of Race and Democracy in the Nation’s Capital (2017); an older but detailed study is Constance McLaughlin Green’s The Secret City: A History of Race Relations in the Nation’s Capital (1967).

And don’t forget that all Patowmack Packet articles are available on the website.

One person who had an enormous impact in spots was Lady Bird Johnson. He influence was to great extent simply by having huge drifts of flowers and bulbs planted along places like the GW Parkway. In the spring, when you pass by the millions of daffodils, think of her.