Welcome to so many new subscribers! Thanks for joining the Patowmack Packet, and I hope you enjoy the articles (and do recommend it to friends).

Summer in the National Capital means three things: under-.500 baseball, Congressional recess, and the arrival of the tourists. Nearly 26 million tourists descended on Washington, D.C., in 2023, setting an all-time record. The majority of those visitors spent their time in the city’s so-called “monumental core,” centered on The National Mall. Touring the U.S. Capitol, Smithsonian museums, Library of Congress, Washington Monument, Lincoln and Jefferson Memorials, and Arlington National Cemetery, and gawking at the White House through the ever-growing security fence, is a time-honored rite of passage for American 8th-graders, a favorite family vacation, and a must-do for foreign visitors.

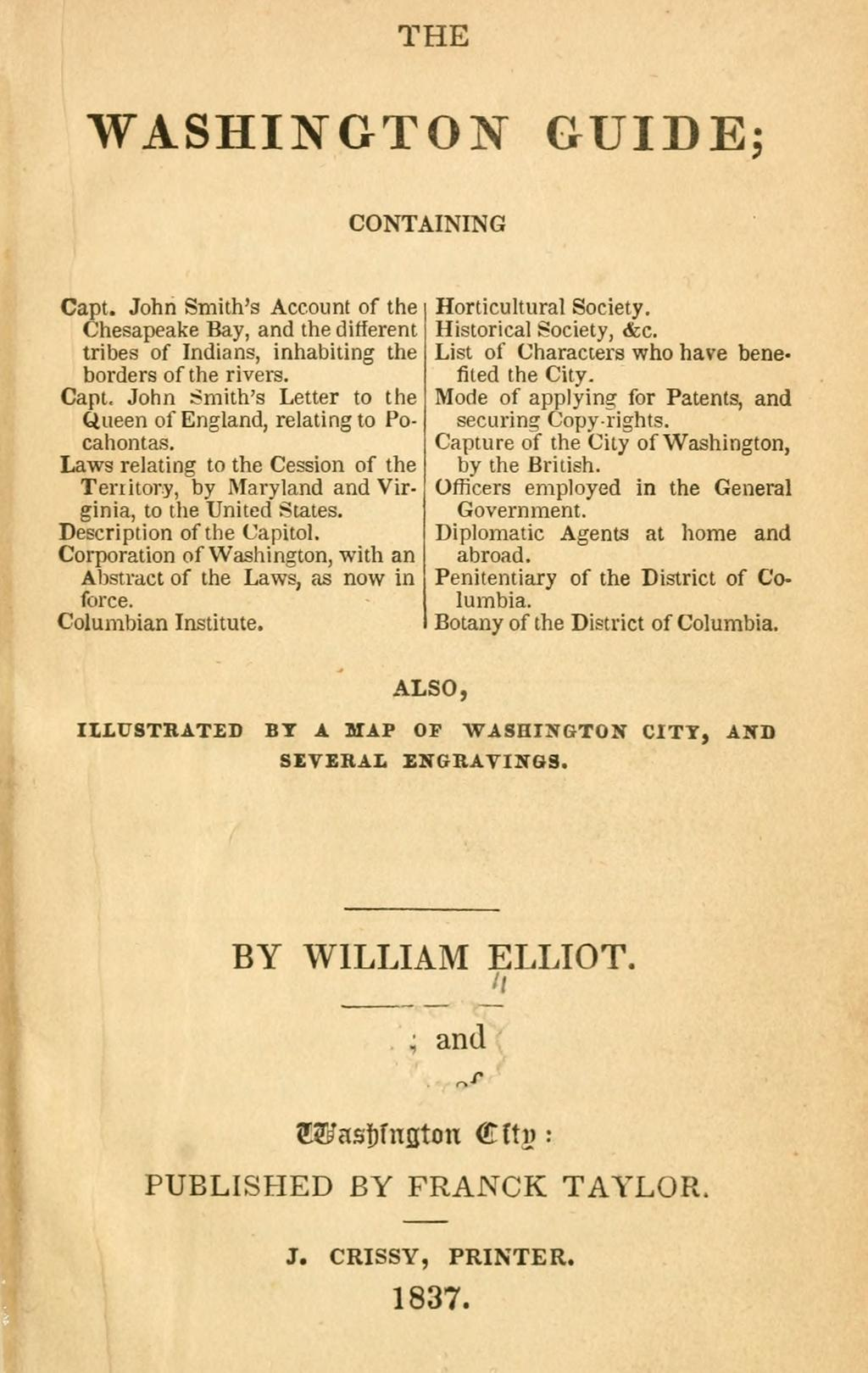

Tourism has been a central part of life in the National Capital since the mid-19th century. Indeed, as early as Andrew Jackson’s presidency, an enterprising clerk in the Patent Office named William Elliot published in 1837 the Washington Guide, which included descriptions of the city and its sparse number of public buildings.

(William Elliot, The Washington Guide, 1837; image from Library of Congress)

By the early-20th century, tourism was an established industry in the Capital, and Washington guidebooks were appearing yearly, from Keim’s Illustrated Hand-Book: Washington and its Environs to the Rand McNally & Co.’s Handy Guide to the City of Washington, which were sure to list the most popular hotels and restaurants in the city. Also popular were souvenir volumes for presidential inaugurations and business conventions, all profusely illustrated with photographs of the newest government buildings.

Anyone who visits the Capital sees immediately that it is a planned city, not an organic growth like London or Jerusalem. But who decides what Washington is, what those tourists see and what Washingtonians have to live with? Few visitors, and maybe not so many District residents themselves, likely know that Washington looks the way it does thanks to a small number of federal and municipal bodies. Among them, one of the most important is the National Capital Planning Commission, (NCPC), which celebrated its centenary on June 6, 2024. These groups make the sometimes lauded and sometimes controversial decisions that, in the words of the NCPC, “translate the country’s democratic ideals into physical form.” Their visions and decisions reflect the changing state of the country, its collective or contested history, its expectations for the future, and its never-satisfied feelings about the present.

What the tens of millions of tourists look at today while clutching the modern descendants of William Elliot’s guidebook is a city that, more than any other time since its founding, reflects the intentions of its planner, Charles Pierre L’Enfant. For much of its history, in fact, Washington only partially and fitfully followed the grand design L’Enfant presented to George Washington in 1790.

To take perhaps the most striking example, today the National Mall is a vast expanse of open green space, stretching over a mile from the Capitol to the Washington Monument and another mile to the Lincoln Memorial. The site of presidential inaugurations, festivals, concerts, and even solar eclipse viewings, it is known colloquially as the “Nation’s Front Yard.” Yet a visitor to the Mall a century ago, in the years after the Great War, would have looked upon a scene almost unrecognizable to us: “temporary” government buildings filling the space, a heating plant and two smoke stacks directly in front of the Capitol, what greenery was left covered by stands of trees. A few years before that, and the tourist coming to Washington may well have detrained on the Mall, at the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad terminal whose tracks ran right onto the once-open area (and where today stands the National Gallery of Art).

(The Mall, circa 1920; Harris & Ewing, photographer, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

That Washington now embodies far more closely L’Enfant’s design is due to the seminal work of the McMillan Commission. As Washington celebrated its centenary in 1900, the gap between L’Enfant’s plan and reality brought forth calls for the “improvement of the District of Columbia in a manner and to an extent commensurate with the dignity and the resources of the American nation,” in the words of the subsequent report. In 1901, a congressional committee, chaired by Michigan Senator James McMillan, was charged with developing a comprehensive park system for the city that would bring back the “beauty and dignity [of] the original plan of the City of Washington.” The Commission’s report, released the following year and commonly referred to as the McMillan Plan, set the template for a much broader re-envisioning of Washington’s public spaces, centered on the Mall, and returning the city fundamentally to L’Enfant’s concept.

(Segment from McMillan Plan for the National Mall, 1902; image from National Endowment for the Humanities)

If there was a guiding spirit influencing the McMillan Commission’s report, it was the “City Beautiful” Movement, the great trend in early 20th century American urban planning. Municipal improvement became a critical need as American cities exploded in size and population during the last decades of the 19th century, thanks to massive immigration from Europe and the post-Civil War industrial boom anchored by John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil, Andrew Carnegie’s Carnegie Steel, and J.P. Morgan and Company.

The City Beautiful (as the movement was often called) combined utilitarianism with aestheticism, seeking not just better public sanitation or safer roadway, but inspiring vistas, grand shared public spaces, and soaring architecture. Visionaries like Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr. and Jr., and Daniel Burnham, and partnerships like McKim, Mead, and White expressed through a neo-classical idiom a refined yet democratic concept of what American cities should look like. Many of these leading lights converged to make the 1893 World’s Columbia Exposition in Chicago the greatest laboratory of City Beautiful concepts ever achieved. The stunning “White City” had a profound effect on urban planning for a half-century, up to World War II, and vestiges survive to this day in Chicago’s famed Museum of Science and Industry, housed in what was the Exposition’s Palace of Fine Arts.

(The White City, Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition, 1893; image from Chicago Architecture Center)

The aesthetics of the City Beautiful found fertile ground in the National Capital, whose design by L’Enfant shared in spirit, if not in time, many of the same goals of monumental architecture. The connection became explicit when Sen. McMillan authorized a Park Commission of leading Beaux Arts architects, Daniel Burnham, Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., Charles McKim, and Augustus St. Gaudens, along with influential secretary Charles Moore, to craft his committee’s formal report.

There was perhaps no more distinguished architectural and artistic commission in American history. Burnham was the man most responsible for shaping the Columbian Exposition, as its Director of Works, while Olmsted was carrying on his father’s legacy as the leading landscape architect in America. McKim had graced Boston with its public library and Rhode Island with its capitol building, while St. Gaudens was the greatest American sculptor of the age, famous for the haunting figure “The Mystery of the Hereafter and The Peace of God that Passeth Understanding,” also known as “Grief,” which marks the grave of Marian Adams, wife of historian Henry, in Washington’s Rock Creek Cemetery.

(“Grief,” by Augustus St. Gaudens, Marian Adams’ grave in Rock Creek Cemetery; image from Library of Congress.)

After touring several European capitals, including Rome and Paris, the Park Commission released its report in January 1902. The McMillan Plan came at a moment of technological transformation that was reshaping American life. Electricity lighted up dark interiors and ended the tyranny of night, creating new concepts of time and public space. Electric streetcars started reshaping cities, allowing the wealthy to move out of the cramped urban center and build suburban communities in what had been rural areas. Soon, the automobile was to even more dramatically free middle- and upper-class city dwellers from reliance on human or animal power for transportation, while leaving the working class of all races in crowded and neglected urban enclaves. Even the use of greenspace in cities was being reconsidered, and the McMillan Plan emerged just as the decades-old battle to create Rock Creek Park had been won, adding thousands of acres of nearly pristine woodland in the middle of Washington to be integrated into the overall vision of reshaping the city’s core along L’Enfant’s original lines.

(Map of Rock Creek Park, 1916; image from Library of Congress)

To try and bring the Park Commission’s recommendations to fruition, Congress created a number of federal bodies to review and weigh in on development. The earliest was the Commission of Fine Arts, established in 1910 to advise on the design of public buildings including monuments such as the Lincoln Memorial and government infrastructure like the massive Federal Triangle. Comprised of seven prominent artists and architects, along with a small staff, the CFA quickly became the most powerful arbiter of public aesthetics in the National Capital, setting the standards for civic art, its status cemented by the success of the Lincoln Memorial.

(Dedication of Lincoln Memorial, May 30, 1922; image from National Park Service.)

In an era of Progressives such as Herbert Croly and Walter Lippmann, who championed expertise as necessary for the strengthening of federal government and national institutions, it’s doubtful that there were any critics at the time who thought it somewhat ironic that a commission charged with shaping public art in the capital of the world’s largest democracy was itself unelected and unanswerable to the people. In some ways Charles Moore, former secretary of the McMillan Commission, became the representative and most powerful member of the CFA, serving for three decades, from 1910 through 1940, and from 1915 to 1937 as the Commission’s chairman. It was during Moore’s chairmanship that planning for the Federal City’s monumental core reached its apogee, particularly with the Federal Triangle.

(Image from CFA)

As the federal government continued to grow in size, a different body was needed for the more prosaic, but no less important task of overseeing the expansion of government offices within the District’s urban setting. The CFA was followed in 1916 by the Public Buildings Commission, charged with guiding federal office construction, and whose descendant is the little-known, but extremely powerful General Services Administration.

The CFA and Public Buildings Commission, along with the Army Corps of Engineers and the presidentially-appointed commissioners of the District of Columbia, oversaw the planning and development of Washington as the American Century began in earnest. Yet before long, the orderly goals of the McMillan Plan faced an unexpected threat. The sudden and massive growth of the Capital during World War I included an inundation of hundreds of thousands of “Great Warriors” to run the new war machine. This not only strained Washington’s resources to the breaking point, but the burst of construction of temporary and permanent structures alike threatened to overshadow the Plan’s vision for the monumental core. By the mid-1920s, the need for a new organization to guide development in the District and revitalize the Plan was evident.

Read Part 2 of this series: “The National Capital Planning Commission Turns One Hundred.” And, don’t forget that all the Packet’s articles are available for free here!

Further reading: For the CFA, see Thomas Luebke, Civic Art: A Centennial History of the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts (CFA, 2013), a massive and beautiful volume; on Charles Moore, see Pamela Scott’s essay in the same volume. For the last great neo-classical designer, see Steven McLeod Bedford’s John Russell Pope: Architect of Empire (Rizzoli, 1998). Also very useful is Richard Longstreth, ed., The Mall in Washington, 1791-1991 (National Gallery of Art, 1991). For the Federal Triangle, see Sally Kress Tompkins, A Quest for Grandeur: Charles Moore and the Federal Triangle (Smithsonian Institution, 1993). On urban planning in the early 20th century, see William H. Wilson, The City Beautiful Movement (Johns Hopkins, 1989), though it has little on Washington.

I hope your post on the National Capital Planning Commission will also cover some of its less laudable decisions such as the taking of Fort Reno