What Rocks!

A bit more on Washington's natural treasures: the Great Falls and Rock Creek Park

The layman’s exploration of Washington’s physical geography in my last post may not quite have captured how the area’s striking natural features help shape life in the National Capital. As unique as is Washington’s topography, it is not something sublime and remote, like the Tetons or the Grand Canyon. Nor is it entirely hidden beneath concrete, asphalt, and artificial landscaping. Rather, it is part and parcel of Washingtonians’ public and recreational patrimony, and perhaps as much a source of civic pride as the monumental core of the city itself.

No other major world capital has such spectacular natural areas within its boundaries or as close by as does Washington. Just fifteen miles from the National Mall as the crow flies are the stupendous Great Falls of the Potomac (I talked a bit about its history as a national park in my post on the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal). One of the great geological formations on the East Coast, the Falls welcome nearly half a million visitors a year, according to the National Park Service. Carved out of the bedrock of the Potomac River for eons, the Great Falls mark the beginning of the transition of the river from the rocky cataracts to the tidal estuary that begins a little further down, past the Little Falls and at Chain Bridge.

(The Great Falls from the Maryland side; photo by the author)

Like Niagara Falls, the Great Falls can be accessed from two opposite vantage points, on the Virginia and Maryland sides of the Potomac. On the Virginia side, three viewing platforms give slightly different angles of the falls and bring one extremely close to the cataract. In the expansive park, one can walk the preserved portions of George Washington’s Patowmack Canal which skirt the Falls (which I discussed here). A bit further on, a moderate hike leads to the extraordinary Mather Gorge, where the river is channeled through a narrow chasm. The multiple geological layers of bedrock terrace, Piedmont uplands, and old and new flood plains reveal outcroppings of metagraywacke (a type of metamorphosed sandstone), dark amphibolite, and glittering mica schist, among other rocks, all fractured and jointed over the millennia.

(Mather Gorge, on the Virginia side; photo by the author)

On the Maryland side of the Falls, one is properly at the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park. Here, the locks and Great Falls Tavern, now a visitors center, are particularly well-preserved, along with the towpath, which runs the entire 184-mile length of the Canal. To reach the Falls proper, cross Olmstead Island, which was once the Potomac riverbed and is now a protected biological habitat, with its impressive, deeply cut rushing channels on either side. Surrounded by such scenery, Washington might seem hundreds of miles away, but from here, you could walk the C&O Canal towpath all the way downriver into Georgetown where it meets the Rock Creek as that powerful stream empties into the Potomac.

The Rock Creek Valley is the undisputed geological and public treasure within the confines of the District of Columbia itself. As former British Ambassador Lord James Bryce proclaimed in an address to the Committee of One Hundred on the Development of Washington, D.C. (and later published in National Geographic Magazine), “[t]o Rock Creek there is nothing comparable in any capital city in Europe.” In few other world cities is there a similarly expansive tract of nature.

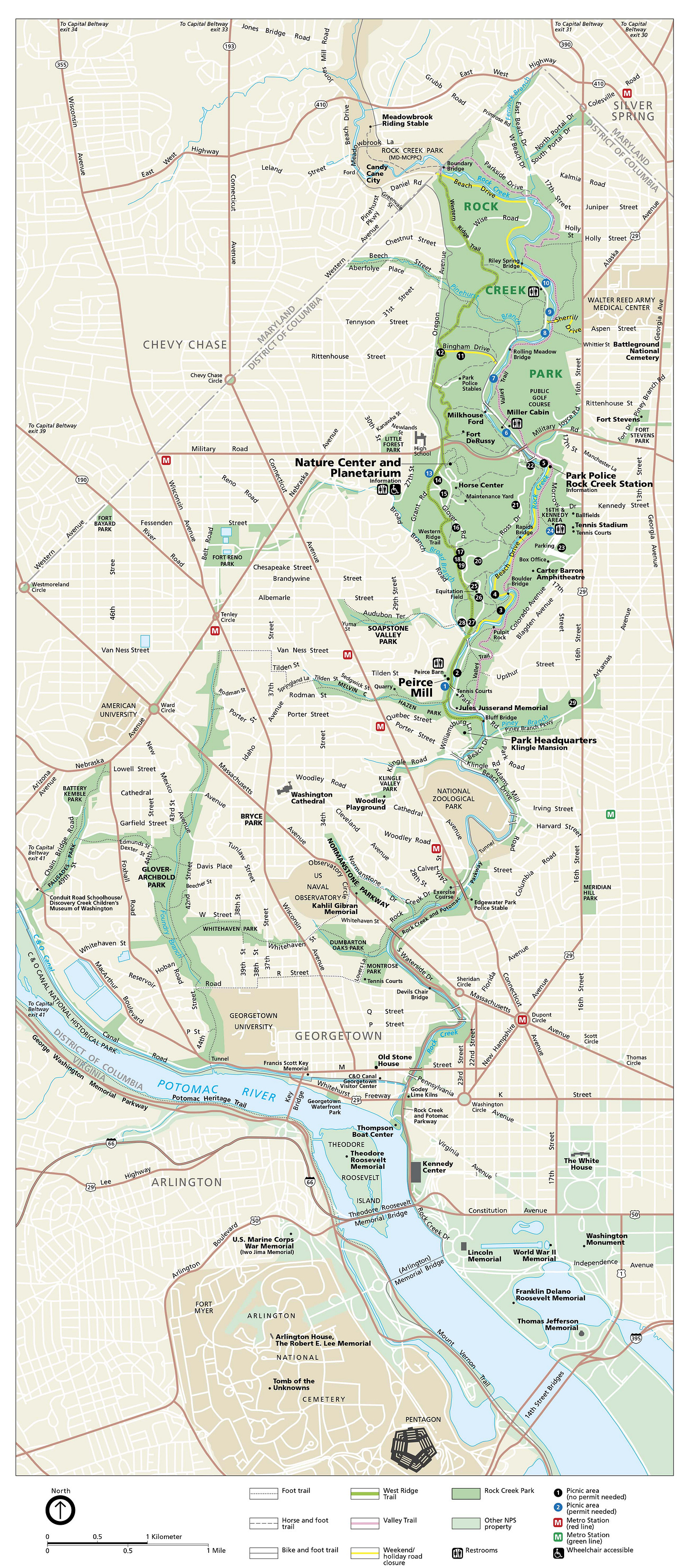

Cutting nine miles through the District on a north-south axis, the Rock Creek empties into the Potomac just west of the Watergate Apartments. It was the dividing line between independent Georgetown and the Federal City from 1790 until the two were amalgamated in 1871. The creek itself is a 33-mile watercourse that rises in suburban Montgomery County, Maryland, but its most spectacular sections are in Washington, where the deep valley is surrounded by forest, tall hills, and outcroppings of Piedmont rock overlain by alluvial deposits along the Creek. The swiftness of Rock Creek’s stream led to the building of no fewer than eight mills of varying operations during the 19th century. Today, only the Peirce Mill, built in the 1820s as a grain mill, remains as a history museum.

(Stone bridge, on Beach Drive, in Rock Creek Park)

Originally proposed in 1866, it took more than 20 years for the U.S. Government to approve the purchase of Rock Creek as an urban park, the first national park inside a city’s limits. Thanks largely to the efforts of Washington banker and philanthropist Charles Carroll Glover and Sen. John Sherman of Ohio (of Sherman Anti-Trust fame), the bill setting aside the Park was passed and signed by President Benjamin Harrison in 1890. The Park today consists of 1,754 acres, though adding in the contiguous Rock Creek Regional Park in Maryland includes another 1,800 acres. The Park’s southern boundary is at the Klingle Ford Bridge, where the National Zoological Park begins. From there southward, the Rock Creek and Potomac Parkway, constructed in stages between the mid-1920s and 1935, preserves the watercourse down to where it empties into the Potomac, at the Thompson Boat Center, though in scenery not nearly as spectacular as the Park itself.

From the Park’s founding in 1890 until 1933, it was administered by the U.S. Army’s chief of engineers, though the District of Columbia’s Commissioners (in the days before home rule) also supervised park management. The military ran the Park, laid out the roads, and determined what would be built inside the Park and where. In this, it largely followed the recommendations of the Olmsted Report, completed in 1918 as a follow-on to the famous McMillan Plan of 1902 that shaped the park system and public space of the National Capital. Among the more notable of the military administrators was the last, Col. (later Maj. Gen.) Ulysses S. Grant III, who managed the Park from 1925 through 1933.

Over a century of use has altered the Park, of course, but the degree of preservation is perhaps unprecedented for such an expanse within a major urban center. Rock Creek’s magnificent landscape forged a unity among public officials not always evident in large public works projects. As the Olmsted Report asserted in its opening sentence: “The dominant consideration, never to be subordinated to any other purpose in dealing with Rock Creek Park, is the permanent preservation of its wonderful natural beauty, and the making of that beauty accessible to the people without spoiling the scenery in the process” (quoted in Barry Mackintosh, “Rock Creek Park: An Administrative History” (NPS, 1985), p. 40).

The National Mall may be the Capital’s answer to London’s urbane Hyde Park and Paris’ elegant Jardin des Tuileries, but Rock Creek Park is as close as one can get to the experience of raw nature irrupting in the middle of a major city. Perhaps the Park in some way reflects the enduring hold on Americans’ imagination of the rugged expanse of their continent, of the Rocky Mountains, the Grand Canyon, and the great rivers. Less than a mile from the ordered landscape of the Mall, one might imagine it celebrates in miniature the extraordinary natural bounty that pulled American settlers across valleys, plains, and deserts to the Pacific Ocean. Perhaps it is no coincidence that the Park was established just as the Census Bureau announced that the American frontier had closed, ending one epoch in our national life and beginning another.

Among the millions who have enjoyed Rock Creek Park have been prominent politicians and officials, likely the most famous being President Theodore Roosevelt. Roosevelt was an inveterate fan of the Park, regularly bringing his young family to hike, swim, horseback ride, or sled its wilderness. He recalled in his Autobiography that “we liked Rock Creek for these walks because we could do so much scrambling and climbing along the cliffs…” (quoted in Mackintosh, p. 32). Roosevelt often was accompanied by the long-serving French Ambassador in Washington, Jules Jusserand, who similarly treasured the Park, as did the aforementioned British Ambassador Lord Bryce.

(National Archives photo of Teddy Roosevelt, likely in Rock Creek Park)

One anecdote illustrates both how Rock Creek was Washington’s “backyard” and how parochial the National Capital was in the days before America became a world power. Sometime before 1906, a young Henry Stimson, lawyer from New York, was down in Washington on business and decided to go horseback riding in the still-undeveloped park. That day, the Rock Creek was swollen and turbid from recent rains. From across the creek Stimson heard a hail. It was fellow New York lawyer Elihu Root, now the Secretary of War and first of the “wise men,” riding horses alone with President Roosevelt. Root called Stimson over, but the young lawyer hesitated to cross the raging stream. Suddenly, Root bellowed, “Mr. Stimson, the President of the United States, through the Secretary of War, orders you to report.” Stimson spurred his mount and plunged through the stream, impressing the President and launching him on his storied career of public service. Such days of informality among Washington’s elite in an urban wilderness, without cars and hardly any roads, is all but impossible to imagine now.

(Teddy Roosevelt leaving the White House for a horseback ride)

In 1933, Teddy’s cousin, Franklin D. Roosevelt, transferred administration of the Park to the National Park Service, in a reorganization which saw the NPS take over control of U.S. national monuments and battlefield parks. Managing the pressures of urban development along the edges of the Park, especially on the heights overlooking the valley, mitigating water pollution from Maryland and the District, and easing overuse and misuse of the Park has been a constant focus of the National Capital Parks division of the NPS for the past nine decades.

Balancing the needs of a modern city with preserving Rock Creek’s nature has produced some notable results. The graceful Taft Bridge, which continues Connecticut Avenue over the Park, spans 900-feet, and took a decade to build, from 1897 to 1907; and the lovely stone bridge at a bend on Beach Drive, are just two examples of trying to maintain natural beauty with functionality. On the other hand, the unavoidable roadways next to Rock Creek in the valley bottom and along some of the high hills scar the scenery, yet can be replaced by no current alternative short of closing the park to all motor vehicles. Indeed, one of the recent changes has been to close five miles of Beach Drive, the main road through the Park, to cars and motorcycles, in the hope of reducing environmental damage to the Park at the cost of inconveniencing commuters to Montgomery County.

Though roads, bridges, parking lots, nature centers, picnic grounds, and paved trails have intruded upon and altered some of the topography of the Park, it remains largely as the Olmsteds imagined it in 1918. Lying at the very eastern edge of the Piedmont Plateau before it gives way to the lower-lying Coastal Plain, Rock Creek is both a treasured retreat and an eternal reminder of the unique geology of the National Capital.

Bonus question: Tea with me at the Cosmos Club for the reader who correctly identifies the reference and original of this post’s title.