Just south of the 16th Street Bridge, which crosses the Piney Branch of the Rock Creek in Northwest D.C., stands the looming Woodner Apartments. Built in 1952, the large complex once counted Bob Hope and John F. Kennedy as residents. Walk down the sidewalk to the southern wing of the sandstone-colored building and stand at the service driveway that separates the Woodner from the Oaklawn Apartments next door. Here, a few feet below your shoes, meet two physiographic regions of the United States, the Appalachian Highlands and the Atlantic Plain.

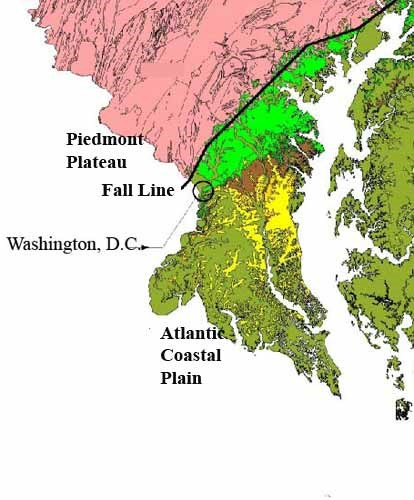

Since there are only eight physiographic regions in the entire continental U.S., this is a major geological spot. To be more precise, the two physiographic regions on which Washington, D.C., lies are themselves divided into provinces, which determine the local geology and topology (there are 25 provinces in the continental United States). What you’re really standing on at the Woodner, is the border of the rocky Piedmont Plateau of the Appalachian Highlands and the sedimentary Coastal Plain of the Atlantic Plain.

You can’t really tell that this is the border of two geological regions, but if you look northward from the Woodner, Sixteenth Street crosses the bridge with its four guardian tigers and gently undulates as it rises up to the District line and on into Maryland. Pivot around, and you look down the arrow-straight road descending to the White House, exactly two and half miles away, and the Potomac River beyond. Stretching away from you unseen on a diagonal to the northeast and southwest, the geological border continues all the way up to Canada and down to Georgia before curving westward to parallel the Gulf of Mexico.

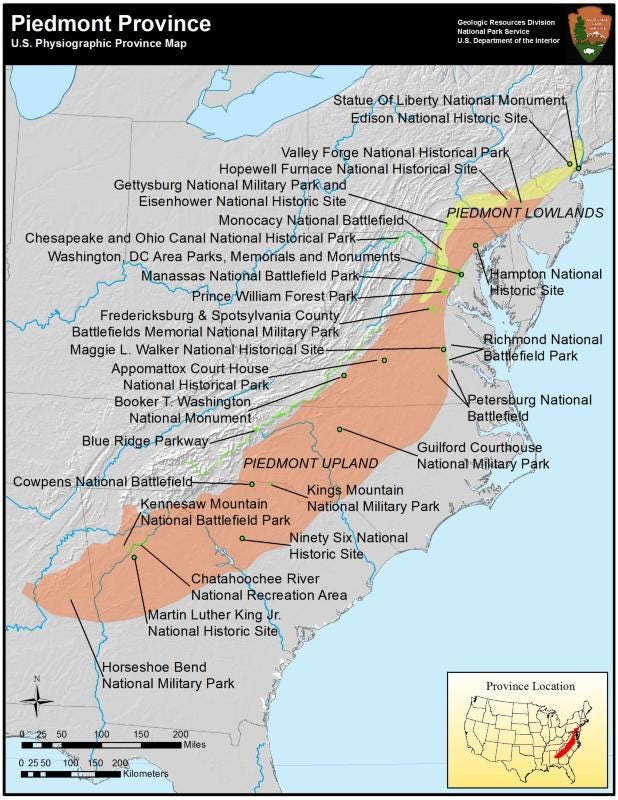

Though Washington, unlike almost all major cities, contains two physiographic provinces, both Maryland and Virginia are far more geologically diverse. In the Mid-Atlantic area, the Appalachian Highlands contains four provinces. Moving west from the Piedmont Plateau, one reaches the Blue Ridge province, then the Valley and Ridge, and finally the Appalachian Plateau and its mountains, before the Appalachian Highlands gives way to the vast Interior Plains region that stretches from western Ohio to the edge of the Rocky Mountains.

To the east, the Coastal Plain meets the Atlantic Ocean about 120 miles from Washington, measured by a roughly straight line from the District to Rehoboth Beach, Delaware. Then, the Continental Shelf extends the Atlantic Plain into the ocean for an average of 135 kilometers before dropping off to the oceanic depths. Both Virginia and Maryland encompass all these provinces, to varying degrees. Washington, D.C., however, has just the two, the Piedmont and the Coastal Plain, but those two make it unique among major world capitals.

(Physiographic provinces in southern Maryland)

If you’ve hiked along the Great Falls of the Potomac, in Rock Creek Park, or on the Northwest Branch in Montgomery County, you’ve clambered over massive rocky outcroppings of the Piedmont Plateau that are over 500 million years old, dating from the Early Cambrian era (if you go a bit farther north, towards Baltimore, you can see outcroppings of Baltimore Gneiss, over a billion years old).

Topographically, the Piedmont is marked by hard, rocky, rolling hills, cut by steep river valleys. The rocks of the Piedmont are igneous and highly metamorphosed, including hard gneisses and mica schists, often foliated (striped), and shimmering in the sunlight, with numerous outcroppings of quartz. Along with numerous other formations, the Laurel and Sykesville Formations account for much of the hard Piedmont rock in the D.C. area. It stretches all the way to the Blue Ridge, roughly at Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia, sixty miles away. As it moves westward, the Piedmont rises up several hundred feet in the Washington region, topping out at 518-feet at its peak at Tysons Corner, in Virginia. The heights above the Potomac where Georgetown sits and along the Palisades are in the Piedmont rise.

Returning to the Woodner Apartments on 16th Street, as you move southeast into the Coastal Plain, the rocky outcroppings disappear, and the topography begins to level out. Here, millions of years of sediments from the Coastal Plain cover the Piedmont bedrock and dip down towards the Chesapeake Bay and ultimately the Atlantic Ocean. In Washington and its suburban counties, the sediments fan out along the border of the two provinces, which is why there is no abrupt shift between the two geological sections. The sediments over the Piedmont bedrock are mainly unconsolidated sand, gravel, and clay. They measure from a few inches thick at the Woodner Apartments to 1,800 feet just outside Washington, and reach 8,000 feet in thickness at the Atlantic coast. (General information from Paul M. Johnston, Geology and Ground-Water Resources of Washington, D.C., and Vicinity (US GPO, 1964)).

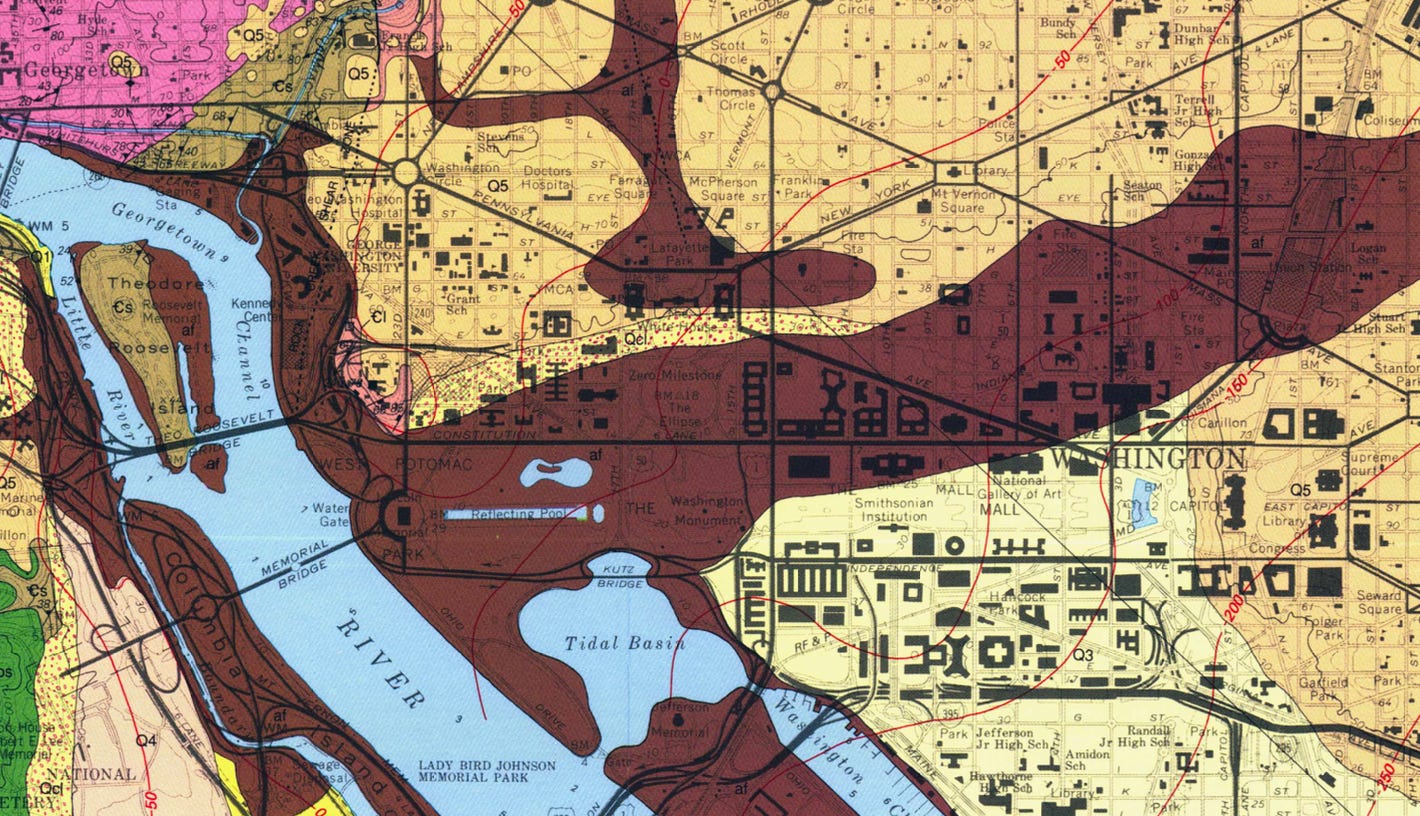

The District is not entirely level in the Coastal Plain, of course, for both the Capitol and the White House were built on rising land. Federal City planner Pierre L’Enfant chose Jenkin’s Hill for the site of the Capitol, memorably calling it “a pedestal waiting for a monument.” George Washington himself selected the location for the President’s House, on a small rise opposite what would become Capitol Hill. The stylized N.C. Wyeth painting below shows Washington with James Hoban, architect of the White House. Barely discernible in the background is the Potomac, which in the late-18th century came up close to the mansion’s grounds.

Two-thirds of Washington lies in the Coastal Plain, but large swaths of the city, running west to east from the Potomac through the Lincoln Memorial and Washington Monument, the White House, Ellipse, Federal Triangle, Penn Quarter and on past Union Station are all artificial landfill (as seen on the USGS map, below, in dark brown).

These low-lying areas of Coastal Plain sediments are the real reason Washington was originally marshy, especially at the tidal flats along the Potomac. Only the landfill made possible the building up of much of the monumental city over the past two centuries. More recently, both the 1902 McMillan Plan’s design for Washington’s core and the Hoover-Roosevelt development east of the White House depended on land filled or reclaimed that could support massive building projects. What to the millions of tourists who visit Washington each year looks like a static landscape has been constantly evolving, expanding, and reshaped to fit the needs of the National Capital.

Next up: some thoughts on Washington’s geological treasure, Rock Creek Park.

“Here, millions of years of sediments from the Coastal Plain cover the Piedmont bedrock and dip down towards the Chesapeake Bay and ultimately the Atlantic Ocean.” Which is why the coast of VA and MD around the Bay are one of the great shark teeth collecting locations in the world.

Excellent--places to go this summer. Never would have thought "Sharks Tooth Island" was a good place to get...shark's teeth. Just drove past Westmoreland State Park the other weekend, but didn't stop.