VA250: The Motor of the Revolution

A multi-year civics lesson in preparation for the Semiquincentennial

“Virginia has the sword, the pen, and the voice of the Revolution.” So argues Cheryl Wilson, the enthusiastic executive director of the VA250 Commission. She is referring, of course, to George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and Patrick Henry, the leading Virginians who drove forward the movement for Independence during the 1770s.

Created by the Virginia Legislature in 2020 to commemorate the Semiquincentennial of Independence, the VA250 Commission has been coordinating or sponsoring numerous events since 2023. The Commission will continue through 2032, marking the entire anniversary span of the Revolutionary War, through the surrender of Lord Cornwallis’s army at Yorktown, Virginia, and the subsequent Treaty of Paris that ended the war.

While there are 250 commissions in every State, VA250 has a good claim to be the preeminent state organization, though Massachusetts would dispute that, much as the two colonies vied for leadership back in 1776. “It’s appropriate the Virginia is leading semiquincentennial celebrations, since Virginia led in founding the Nation,” argues Wilson. The initial drivers for forming the Commission were organizations including the Virginia Museum of History and Culture, the Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation, Colonial Williamsburg, and some of the historic houses in Virginia. Its national honorary chair is Carly Fiorina. Much of the energy is found in the 134 Virginia localities running 250th programming, Wilson tells me, and in city and county-level commissions throughout the Commonwealth. Essentially, there is at least one event each week happening somewhere in Virginia.

(Image from VA250 Commission)

The activities of VA250 offer a multi-year civics lesson, one that hopefully will spark greater interest in the Revolution. Residents of the Old Dominion may also hope that the commission’s efforts will give a more balanced view of early American history. Generations of American schoolchildren have received a Massachusetts-centric version of colonial history, from the Pilgrim “Fathers” through Paul Revere, thanks to the long dominance of Bay State historians, writers, and poets. Unlike in Massachusetts, where Boston dominated both the colony and historic events, colonial Virginia had no urban center; even with Jamestown and Williamsburg, the plantations and farms of the colony led to a largely dispersed social and political structure. The historical eye can focus more easily on Boston Harbor and Faneuil Hall, than it can on the broad Tidewater.

But if Massachusetts has long claimed to be the cradle of the Revolution, it was in Virginia that many of the first and critical steps in forming what ultimately became the United States occurred. Jamestown, of course, was founded in 1607, becoming the first permanent settlement in British North America, over a dozen years before the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth. Perhaps even more importantly, organized representative assembly in America began at Jamestown in 1619, predating the Mayflower Compact and its legend of self-government. Some of the most important local statements opposing British oppression flowed from Virginia pens, including the Fairfax Resolves and the Fincastle Resolutions. And it was the Virginia Convention that authorized its delegates to the Continental Congress to offer the first resolution for Independence, duly submitted by Richard Henry Lee, on June 7, 1776.

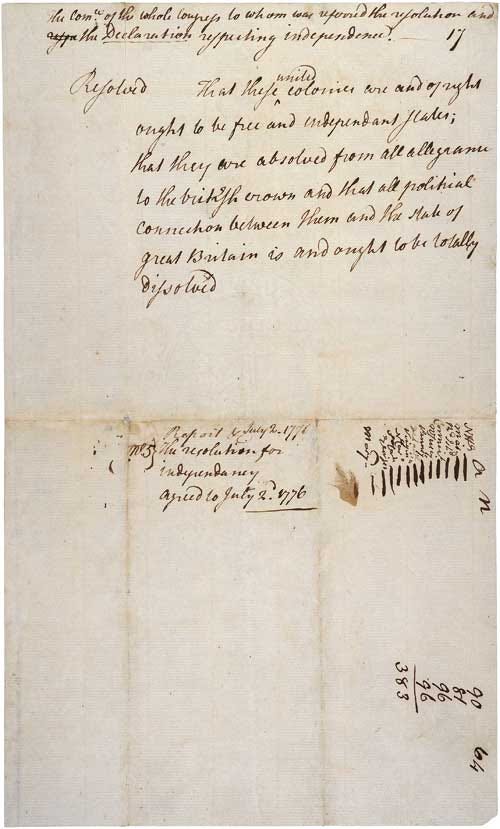

(Richard Henry Lee’s original resolution calling for “Independency,” June 7, 1776, with final tally of the vote on July 2; image from the National Archives)

Were one spoiling for a semiquincentennial spat, one might even say that the Declaration of Independence itself, immortally penned by Thomas Jefferson and comprised primarily of an amalgamation of George Mason’s Bill of Rights, Jefferson’s draft Virginia Constitution, and Lee’s resolution, grew out of the Virginia soil, watered by the often-tempestuous rains of Massachusetts.

Nor can it be forgotten that it was in Virginia that the first Africans were brought to the colonies, to Jamestown, and sold as indentured servants, in 1619. As the VA250 motto proclaims, “Virginia’s History is America’s Story.”

While VA250 has been going strong for close to two years now, commemoration of the War for Independence will kick into high gear throughout the country, now that we’ve turned the calendar to 2025. In April, the outbreak of conflict, at Lexington and Concord, in Massachusetts, will be remembered and re-enacted, and events will peak in July 2026. While there is an America250 Commission, which will organize the formal national commemoration, the vast majority of events, talks, exhibits, parades, and the like over the next 18 months will be organized by the States, which is appropriate, since it was the colonies who came together uniting in a common cause.

“A Common Cause To All” happens to be the name of the annual conference on the semiquincentennial that VA250 has organized since 2023. This year will be the final gathering of semiquincentennial planners from across the Nation, held like the previous ones in Colonial Williamsburg, on March 24-26. It will be preceded on March 23 by a commemmoration and reenactment of Patrick Henry’s immortal “Give me Liberty, or give me Death” speech in Historic St. John’s Church, in Richmond.

(Image from VA250 Commission)

For those in the Washington area interested in upcoming VA250 events, a special event on Saturday, January 18, to commemorate the Fincastle Resolutions will take place in Roanoke, in the southwest corner of the State. It’s about 3.5 hours from Washington, so a long, but manageable day trip. At that event VA250 will debut one of its most innovative initiatives, the Mobile Museum Experience. Harking back to the famed “Freedom Train” of 1947 and 1976, the Mobile Museum is a full-scale exhibition in a tractor trailer that will travel throughout Virginia and beyond. A focus of the mobile museum is on schools and local museums, bringing stories of Virginia’s history to younger generations. Communities who want the exhibit to visit can fill out a form on the website linked above.

Those of us old enough to remember the Bicentennial celebrations, way back in 1976, may wonder if the “Spirit of ‘76” remains alive and well in 2026. We are a very different country today from a half-century ago, more diverse, more globalized, more unequal in some ways and more egalitarian in other. Surveys show deep divides over patriotism in America between age groups, with record lows saying they are “extremely” or “very” proud of the country. Nonstop social media bombarding Americans with negative images, dangerous political rhetoric that seeks to divide society, history lessons in school that inculcate pessimism about America, and the difficulties of achieving what used to be considered a normal, middle-class lifestyle, all are challenges to what James Truslow Adams back in the 1930s first called “the American Dream.”

Acknowledging America’s shortcomings does not require delegitimizing the country, its achievements, or its promise. Neither overthrowing our current systems nor encouraging national divorce is an answer. Overcoming such anger and pessimism to bring Americans together as a national community is the key challenge facing everyone involved in the planning for the Semiquincentennial over the next 18 months.

Cheryl Wilson is optimistic, however. We’ve seen huge amounts of interest in the 250th in Virginia, she tells me. Events like the upcoming re-enactment of Patrick Henry’s speech are long sold-out. It remains to be seen just how many people, especially young ones, will tear themselves away from their computer and smart phone screens to participate in live events. But as the VA250 Commission has been showing for the past two years, there is no shortage of opportunity to do so.

Some celebrations are just excuses to have a good time, others have a deeper meaning. Everything connected with America 250 is a important element in maintaining national unity for the next generation. The events, speeches, parades, and exhibits serve as a bridge between our shared past and the more perfect Union that we want to become. The VA250 Commission—and all similar State commissions—are doing a vital service and themselves becoming a part of American history.

While 250 is more than 200; the bicentennial seemed to generate much more public enthusiasm and support. Might the general decline in patriotism have something to do with that?