As you may have noticed, the Packet has been on hiatus since April, though unintentionally. It’s gratifying that a number of readers have asked “what happened to the Packet,” or queries along those lines (such as, “did you quit?”). I’ve been waiting to update you all with an official announcement that would explain why, but we’re still a few months out from that. However, now that summer is over, I thought it was long past time to address the Packet’s silence.

I’m happy to say that the reason is a good one.

Since the spring of 2024 I’ve been full-time (and furiously) researching and writing the first complete history of the Declaration of Independence. Entitled National Treasure: How the Declaration of Independence Made America, the book will be published next spring by Simon & Schuster through their Avid Reader Press imprint. The manuscript is heading into production, I’ve been finalizing the illustrations, and I just received awesome cover art. We should have an official announcement and pre-order link before long.

(Not the cover. The cover is cooler. Image from Natick Historical Society.)

Written for a general audience, National Treasure is the first book to tell the full story of the generations who drafted, preserved, and protected the Declaration; the reformers who enlisted it to create a more perfect Union; the storytellers who popularized it and the scholars who studied it; and even those entrepreneurs who turned it into a perennially popular commodity. It’s filled with dramatic stories, colorful personalities, and little-known episodes in the life of the Declaration.

National Treasure not only covers both the physical and symbolic history of the Declaration—combining two very disparate areas of interest among those who have studied the document—it is the first to fully explore how the Declaration became one of the world’s most famous objects, its image appearing on everything from heroic paintings to handkerchiefs. And as a teaser, among other long-forgotten or never-discussed aspects of the Declaration’s past, it is also the first written account of any kind to ask (and answer) what happened to the scroll during the Civil War. In short, I believe it is as comprehensive a narrative history of the Declaration, and its influence on America, as has been attempted.

It’s fair to say this has been the most intense period of work in my career, completely consuming my waking (and occasionally, my sleeping) hours.

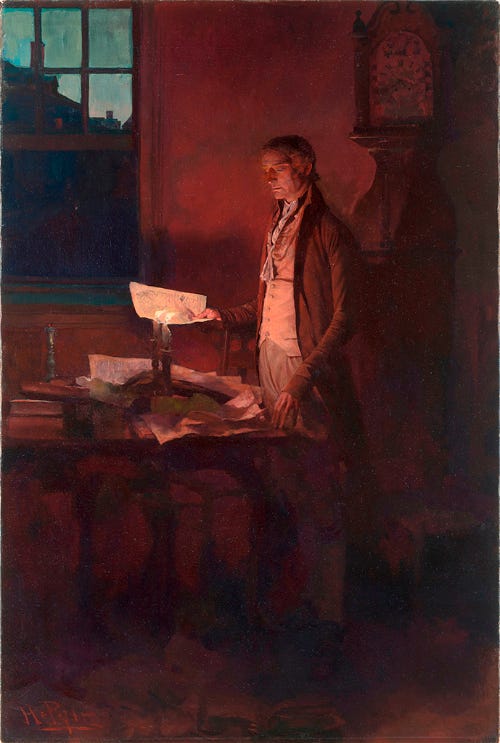

(Not me writing my book—though I’d like to think it’s how I looked—but Howard Pyle’s painting of Thomas Jefferson drafting the Declaration, illustrating “The Story of the Revolution,” by Henry Cabot Lodge, in Scribner's Magazine, March 1898; image from the Delaware Art Museum.)

The amount of assistance I’ve received has been overwhelming, from government departments to archives, libraries to historical societies, and from leading experts in American history stretching from Berkeley to Oxford. I’ve been particularly grateful for a fellowship as a Distinguished Visiting Scholar at the Library of Congress’ John W. Kluge Center, which opened up the Library’s treasure house of holdings (which I hope to cover soon in the Packet).

And it all started with the Patowmack Packet and my longer-term interest in the history of Washington, D.C. Not only is the Declaration’s history largely a Washington story, since the parchment has been in the Capital since 1800 (with a few exceptions well covered in the book), but it was while interested in the architecture of the National Archives that I stumbled on the idea. Over coffee, I asked Colleen Shogan, then the Archivist of the United States, for a good history of the National Archives. She mentioned there wasn’t one and said there were lots of good stories that needed to be told, including when the Library of Congress refused to give the Declaration to the Archives.

I had no idea what she was talking about. Aside from the bureaucratic politics, I didn’t know the Declaration had ever been in the Library. I decided to go get a history of the Declaration in the bookstore on my way out of the Archives.

There wasn’t one.

When I asked at the bookstore, they said they didn’t stock one. I was flabbergasted. One million people a year visit the National Archives and they didn’t have a general history of its most famous possession? And, we were (at that point) just over two years away from the 250th anniversary of both the Declaration and American Independence, and there was no book?

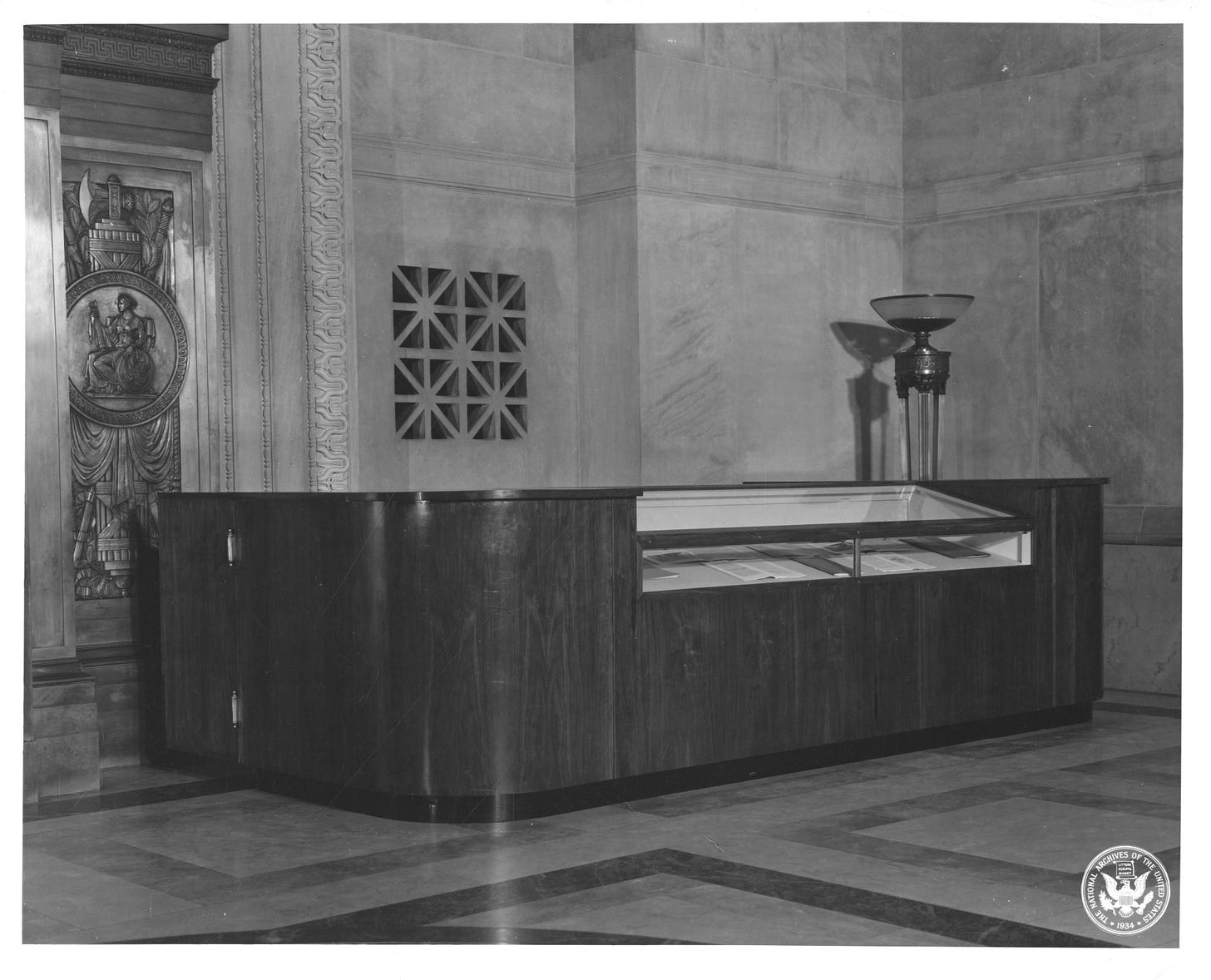

(Where I would have found a history of the Declaration, if there had been one, in the National Archives—in the 1950s. The Facsimile Sales Desk, in 1953. Image from National Archives.)

To make a long story short, I checked for any other histories and found there was nothing recent and nothing that told the whole story. What had been written recently, like Danielle Allen’s Our Declaration, were not general histories. I assumed there were at least half a dozen scholars busily working away in the National Archives on the topic, so I asked Colleen and Jessie Kratz, the wonderful historian of the Archives, how many people they were assisting on just such a book project, and both told me “zero.” Ditto at the Library of Congress.

And that was it. For a writer long looking for “The Story,” I had found it. And I hope you’ll find it as fascinating and inspiring as I have.

Now that the manuscript is finished, it’s good to get back to the Patowmack Packet. Posting may be spotty while I go through the production process, but I’ll be on the lookout for new stories and topics. Given what I’ve been immersed in for the past 18 months or so, you may see the Packet expand a bit into American history more broadly, but it will still try to remain a well-researched, (mostly) original blog, posting what I hope is worthy of your time to read. As always, please do spread word of the Packet, it’s the best way for it to grow.