The British Are Coming! (But Not For Long)

DC250: The American Revolution Institute Brings the War of Independence Back to Life

In May 1783, with the fighting done but the peace not yet signed, officers of the Continental Army formed a fraternal organization at their encampment at Newburgh, New York. Named for the great Roman hero Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus, the Society of the Cincinnati was founded “to perpetuate the memory of the War for Independence, maintain the fraternal bonds between the officers, [and] promote the ideals of the Revolution,” among other goals. George Washington was the first president general of the Society, while his close colleague, the army’s chief of artillery, Henry Knox, was the chief author of the Institution, the Society’s founding document.

(The Institution of the Society of the Cincinnati, with George Washington’s signature; photo from the American Revolution Institute.)

Today, the Society of the Cincinnati has thirteen State constituent societies and an overseas French Society, with approximately 4,600 members. Members are limited to one male from the primary branch of the family tree descending from a qualifying Revolutionary War officer (of which there were only 7,000 or so). Early on defamed by critics with aiming to perpetuate a military aristocracy on the young United States, the Society has maintained its genealogical activities over the centuries while embracing civic education. The Society is housed in the Anderson House, on Massachusetts Avenue, in Washington, D.C., one of the Capital’s most elegant Gilded Age mansions. Run since 2022 by F. Anderson Morse (“Andy” to those who know him), the Society remains one of America’s most venerated fraternal organizations.

(Society of the Cincinnati Eagle, insignia of the organization, c. 1784; photo from the American Revolution Institute.)

Since 2012, the Society also has operated a unique research organization, the American Revolution Institute (ARI). One of the few institutions dedicated to the study of the War of Independence and its era, ARI is poised to begin a nine-year commemoration of the war that birthed the United States. While there will be hundreds of 250th events, such as those run by State organizations like VA250 and MA250, ARI’s focus on the war itself will provide an in-depth look at the battles and personalities of that “vast event,” as the Society’s founders called it. Its program of events will complement the activities of Philadelphia’s Museum of the American Revolution as well as the work of authors like Rick Atkinson, who will release the second volume of his Revolution Trilogy this April.

“We have unique resources” to study the Revolution, notes Executive Director Morse. For well over 200 years, the Society of the Cincinnati has collected materials ranging from Continental Army and Navy records to diaries, mementos, and a host of rare French-language related records (thanks to the French arm of the Society). The Society established a library in 1974, which now has one of world’s largest special collections on the Revolution and the 18th century art of war.

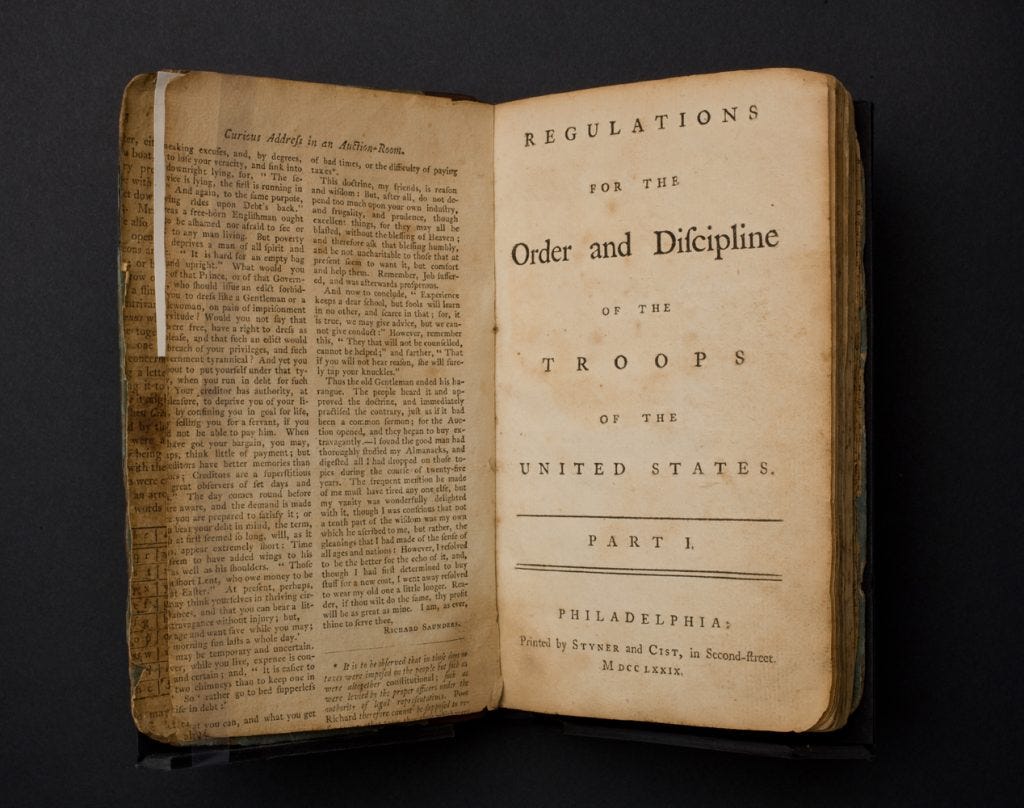

Among the Society’s 50,000 items are treasures including original copies of the military manuals of Baron Von Steuben, used to train the Continental Army at Valley Forge; the handwritten manuscripts of the comte de Rochambeau’s Memoirs (Rochambeau commanded the French forces at Yorktown); and a previously unknown manuscript by French sailor on the warship August, recounting major sea battles in which the French supported Washington’s troops. The library contains 270 items related to the Marquis de Lafayette and 69 items on the Polish military engineer Tadeusz Kościuszko, who created military fortifications including West Point.

(Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United States by Friedrich Wilhelm Steuben (1779); photo from the American Revolution Institute.)

To take advantage of the resources of the library, the Society established a fellows program in 2007 for research in its collections; after its founding, the American Revolution Institute took over the program. ARI has now sponsored over 100 short-term fellows, ranging from graduate students to independent scholars, with roughly a dozen a year. Morse believes that the new, full-year Thomas Jay McCahill III Fellowship, sponsored by the New Hampshire chapter of the Cincinnati with a generous stipend, will attract leading scholars to utilize the resources made available by ARI.

The Society and ARI have long sponsored author talks and other events, and their online reach now is just under one million views on YouTube and nearly 700,000 on other social media. Those who are not scholars, or qualified to join the Society of the Cincinnati (the vast majority of us), yet are interested in supporting and participating in ARI’s mission of educating citizens in the history and legacy of the Revolution can join as an Associate.

For the 250th, the Institute will move to a new level of activity and outreach lasting through 2033, the anniversary of the signing of the Treaty of Paris. Andy Morse reels off an ambitious program of research and events that should appeal to everyone interested in the War of Independence. Annual exhibitions will focus on the battles of that year in the Revolution, starting this year (2025/1775) with Lexington and Concord, Bunker Hill, and the Battle of Quebec. In addition to using its own collection, ARI will bring in objects and artifacts from other partners, including the Museum of American Revolution and Yorktown’s American Revolution Museum. Free, public lectures related to the events of each anniversary year will also be held at Anderson House (located just north of Dupont Circle).

(Anderson House, home of the Society of the Cincinnati, circa 1910; photo from the Society of the Cincinnati.)

The educational element is a prime focus for ARI and Morse. The War of Independence is not taught today nearly as much as it was a half-century ago, and knowledge of it, beyond Lexington and Concord, Valley Forge, and Yorktown, is likely less than that of the Civil War, which still attracts enormous attention. To both educate and inspire a new generation in the Revolution, Morse plans on producing short videos on the war aimed at school-age children. The videos, like the exhibits, will touch on each year of Revolution; one video will give an executive summary of year itself, and five following videos will focus on leading personalities and battles of the war, while also focusing on the principles that drove the colonists to declare their Independence. In all, there will be 54 videos available to use in school lessons on the Revolution.

At a time of political polarization and contesting narratives over America’s founding, the American Revolution Institute is laudably focusing on the great struggle, one which at times seemed hopeless, that gave rise to the United States. Inculcating an appreciation, perhaps even a veneration, for the Revolution and the principles that drove it, is a welcome addition to the civics education planned for the 250th. Given the millions of visitors expected next year in Washington, it is to be hoped that a good percentage of them find their way to Anderson House, to see some of the artifacts from that glorious campaign, to hear from leading experts on the Revolution, and to consider its timeless principles.

The Institute is kicking off its nine-year commemoration of the War of Independence on the evening of Thursday, March 6, with a special reception at Anderson House to open its exhibit on the first year of the conflict, “Revolutionary Beginnings: War and Remembrance in the First Year of America’s Fight for Independence.” Those wishing to attend can find more information here.